“I used to feel as calm in the garden as if I was knitting socks by the fire – it always made me happy”

Spoken to author Lalage (Lally) Snow, these words sum up the peace and fulfillment that can be derived from plants. It is a sentiment well understood by gardeners. Yet this interviewee, and the others featured in her book ‘War Gardens’, tell a story of gardening in conflict’s dark shadow.

From the Gaza Strip to Kabul, from Donetsk to Israeli Kibutzim, from Helmand to the West Bank, Lally dug about to unearth gardeners. Sometimes following leads, sometimes just knocking on doors, she met dozens of gardeners with a unifying passion.

She found the opinions and experiences of her gardeners diverse, but their gardening stories were not. Many grow similar things despite varying growing conditions. The book is punctuated with descriptions of poppies, geraniums, zinnia, tomatoes, peppers, tree fruits and roses, whether grown in the hot dust of the Middle East or the continental temperature extremes of the Ukraine.

The gardeners use the same words to explain what their gardens mean to them – peace, happiness, calm, and relaxation.

One gardener even uses the word ‘safe’ and yet lives with the constant fear of erupting violence and the threat of loss. The need to cultivate regardless is central to every story.

Gardening – a journalistic icebreaker

Bracha Avrahimi, Ma’ale Efrayim Settlement, West Bank, April 2016 Copywright Lalage Snow www.wargardens.org

Lally Snow first went to Afghanistan in 2007 as a self-funded freelance journalist and photographer, picking up commissions from the international press and travelling to many war zones over the next few years.

What made her go isn’t immediately clear but having talked to Lally, she is from a military family and was less fazed by war and combat than others may have been. When starting out as a student photo journalist she decided the best way to learn was in at the deep end.

In the book she describes being gently mocked by seasoned male journalists, who likened her to William Boot, the accidental war correspondent in Evelyn Waugh’s book, Scoop. It is clear that she did experience an element of Imposter Syndrome – she knew her knowledge of the players and terrains of these theatres of war was less than that of more seasoned hacks.

Understanding how and why the violence played out was not her primary motivation, however, rather a desire to amplify the stories of those impacted by war. By using the humanising motif of gardening she’d found a way for war-weary audiences back home to understand the human impact of the events described at a macro level on their news bulletins.

By opening conversations with gardeners, she was also able to talk to people who would not otherwise have spoken to a journalist. By photographing their roses she showed an interest in their achievements. In their green havens, some were able to relax – to talk about the horrors of the past and their hopes and fears for the future.

Gardens of green in the blackness of war

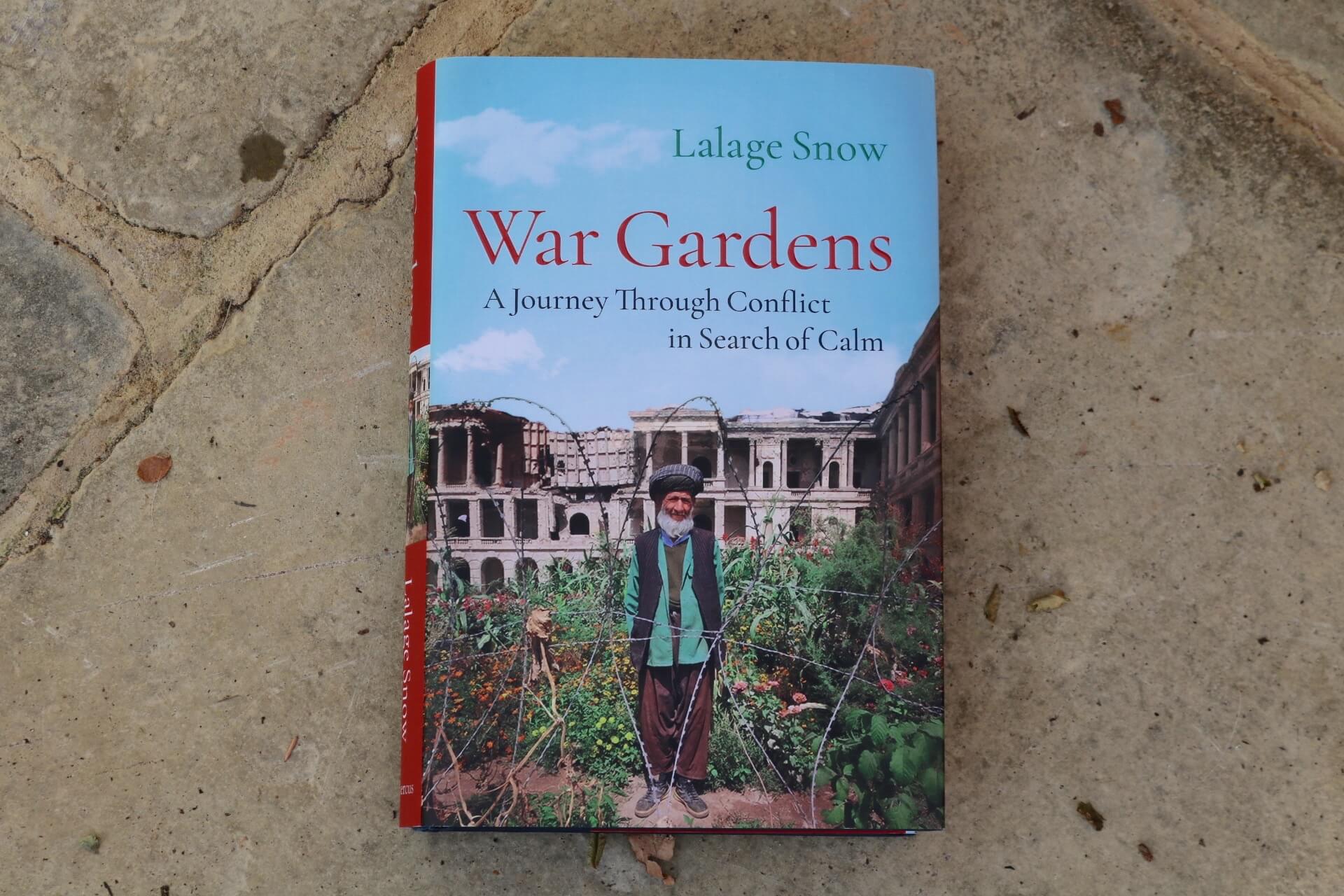

Mohammad Kabir, 105, Darulaman Palace Garden, September 2012 Copyright Lalage Snow www.wargardens.org

The book starts and ends in Kabul, a city with a heritage of beauty and ancient traditions of gardening. Lally meets the head gardener charged with restoring the wasted Babur’s garden in central Kabul, as well as an 105 year old gardener growing vegetables and flowers in the ruined central courtyard of the Darulaman Palace.

Particularly touching also is the story of 18 year old pharmacology student, Hamidullah, who studies surrounded by flowers in his greenhouse and associates flowers with his best friend, killed in the violence.

Further afield she meets a gardener at a military camp in Helmand who grows seeds brought to him by soldiers from across the seas, knowing that should the tide turn and the Taliban return he would lose his life for working there.

In the Middle East, we hear many intriguing gardening stories from Gaza, the West Bank and Israel – from both Jewish and Palestinian gardeners. The unrest here is complex but relates to conflicting senses of belonging and homeland. As such, the sense of grounding that a garden can bring is a microcosm of the roots of conflict here.

We meet the family growing subsistance lettuces and tomatoes several storeys up on a balcony in Gaza. There are growers of cacti, growers of bonsai, and in the West Bank settlements, regimented municipal displays.

The need to put down roots and survive against the odds is a constant theme.

The section on the Civil war still raging in the Donbass region of Eastern Ukraine is particularly enlightening. The war here, an area famous for rose growing, has become a forgotten one – referred to rarely, and usually only in the context of Russia’s wider foreign interventions.

The utter bemusement of those living with rockets falling around them is compelling. Most of the gardeners never thought of themselves as anything other than Ukrainian – the separation between East and West Ukraine a recent and false overlay of identities, and the concept of Civil War bizarre.

We meet Lupvov, an elderly Ukrainian lady, clearly traumatised by her experiences, sitting on her haunches anxiously shelling beans, unable to stop. Her garden, where she grew fruit and veg to enjoy and to supplement her pension, is now destroyed. An ancient pear tree has splintered, her home is obliterated and her future with it. Yet she visits daily, unable to stay away from her ruined haven.

An uneasy but atmospheric read

Beautifully and atmospherically written, this book could never be an easy read. The subject matter cannot allow this. Yet, if you appreciate plants, you cannot help but feel connected to the characters described here, and you will learn something in the process.

You will not understand the finer detail of the Israeli-Palestinian cauldron by reading this book, or the ongoing violence and fear in Ukraine or Afghanistan, but you will gain a greater insight into the people affected by it.

This is not a journey through war by a detached journalist. The gardeners she met in the course of writing this book gave her more than their stories. Just as the water, light and nurture make their flowers grow, so I inferred that their stories gave Lally the motivation and confidence to grow as a writer, film maker and person.

With thanks to Lally Snow for speaking to me and for giving me permission to share her photos here.

War Gardens is published by Quercus and can be purchased through independent network of booksellers Hive by clicking here, Amazon by clicking here or by visiting you local bookshop. www.wargardens.org

I love your blog. Especially, the great Tulip Teacup logo and all the photos. Thanks for the book tip: War Gardens. I’m requesting it now from my library. I too have a blog and invite you to subscribe. It’s title is Be Well, Do Good. It’s found at http://www.be-well-do-good.com

I hope you manage to get hold of the book over there in the US. It really was a thought-provoking read. Thanks also for your lovely comments on my Blog Chuck. The logo sums me up perfectly – gardening and tea. I just looked at your site and loved it. Great musings on such a wide variety of topics – I loved the Disney Solarium although it needs more plants inside! I remembered your name by the way and realised you’d commented on my Alpine Trough post – hope you got round to making one!